AETA

The Australia-East Timor Association (AETA) was established in 1975, following occupation by Indonesia, as an information, solidarity and networking organisation to support the struggle for independence of East Timor. Meetings and rallies were organised and a bookshop established for the distribution and sale of information material on Timor.

East Timor was occupied for 24 years of occupation, becoming independent in 2002 after a UN-supervised referendum in 1999. Independence for Timor Leste was achieved – the main goal of AETA. Questions for AETA then arose – what now should be the focus and goals of AETA? Should AETA focus on humanitarian, social and economic development? AETA conducted a member survey and developed a Strategic Plan to address these issues in 2018.

AETA continues as an information, networking and support organisation in solidarity with the people of Timor-Leste, the East Timorese and wider community in Australia, working on archives, history and commemoration, with the bookshop and Annual Dinner. Several special interest groups have emerged – in Village Technology and Innovation, Education, Health and Communications.

The AETA Strategic Plan focused on the development of information sharing and networking, an online bookshop, seminars, support of knowledge networks and special interest groups, archives, history and commemoration, the Annual Dinner, creation of website to facilitate information sharing, networking and membership regeneration. AETA works mainly in Victoria, and there is increasing interest in supporting related activities in other states.

OUR STORY

The Australia-East Timor Association (AETA) was established in 1975, following occupation by Indonesia, as an information, solidarity and networking organisation to support the struggle for independence of East Timor. Meetings and rallies were organised and a bookshop established for the distribution and sale of information material on Timor.

East Timor was occupied for 24 years of occupation, becoming independent in 2002 after a UN-supervised referendum in 1999. Independence for Timor Leste was achieved – the main goal of AETA. Questions for AETA then arose – what now should be the focus and goals of AETA? Should AETA focus on humanitarian, social and economic development? AETA conducted a member survey and developed a Strategic Plan to address these issues in 2018.

AETA continues as an information, networking and support organisation in solidarity with the people of Timor-Leste, the East Timorese and wider community in Australia, working on archives, history and commemoration, with the bookshop and Annual Dinner. Several special interest groups have emerged – in Village Technology and Innovation, Education, Health and Communications.

The AETA Strategic Plan focused on the development of information sharing and networking, an online bookshop, seminars, support of knowledge networks and special interest groups, archives, history and commemoration, the Annual Dinner, creation of website to facilitate information sharing, networking and membership regeneration. AETA works mainly in Victoria, and there is increasing interest in supporting related activities in other states.

ADVOCACY

AETA’s focus on advocacy issues includes a fair maritime boundary for Timor-Leste, and justice for Witness K and Bernard Collaery.

BOOKSHOP

A core activity of AETA since it was founded has been a bookshop for the distribution of information and advocacy on Timor-Leste. We have held many successful book launches and are currently supplying libraries, universities, schools and bookshops in Australia and Timor-Leste with books from our accumulated stock of over 200 titles.

CELEBRATION

The AETA annual dinner brings members and friends together to celebrate the anniversary of the Proclamation of Independence of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste – 28th November 1975.

INFORMATION, COMMUNICATION AND NETWORKING

Members are notified via email of Timor-Leste related events such as film and book launches, academic and general seminars, conferences and cultural events. AETA disseminates publications about Timor-Leste through the bookshop. AETA encourages members to link with appropriate organisations and projects working in Timor-Leste, along with Timor-Leste Friendship Cities in Victoria and other states.

ARCHIVES

AETA has a significant resource of documents and material reflecting the struggle for Timorese self-determination and independence and AETA’s role in mobilising Australian support. Archiving these resources is being done with the Clearing House for Archival Records on Timor (CHART) led by John Waddingham, with assistance from volunteers.

KNOWLEDGE NETWORKS AND SPECIAL INTEREST GROUPS

AETA has coordinated thematic interest groups to bring people together from different organisations with expertise or interest in a particular area. Members and friends are invited to contact members of the AETA committee if you are interested in joining or hearing more about these groups, including on Village Technology (including Permaculture), Education and Health.

SEMINARS

AETA has organised well-attended public seminars on issues relating to Timor-Leste, usually held at the Victoria University campus on Flinders Street. Seminars have been organised in 2017, 2018, 2019 and are planned for 2020. Subjects include Ego Lemos on “Permaculture” and Michael Leach on “Politics at the Crossroads”, sharing an in depth understanding about the politics which led to the impasse in Timor-Leste resulting in another election being called just nine months after the previous election in mid-2017.

AETA IS AN INCORPORATED ASSOCIATION IN VICTORIA,

WITH THE FOLLOWING OBJECTIVES AND MISSION:

- AETA works in solidarity with the people of Timor-Leste and East Timorese community in Australia

- The Association provides advocacy and information about Timor-Leste to members and public.

- The Association supports specific projects in Timor-Leste and Australia.

(From AETA Constitution – approved 14 August 2014)

A HISTORY OF TIMOR-LESTE

G.J. Burchall

Portugal had run trading posts at Lifau (Oe-cussi enclave) and Dili for at least 150 years before it sent its first governor, Antonio Coelho Guerreiro, in 1702. He fled three years later in the face of repeated attacks by the Topasses, (mixed-race Portuguese), who took no sides but their own.

Over the next decades, the Topass community joined with Timorese chieftains (liurais) to raise an army against the Dutch in Western Timor and assassinated Timor’s Portuguese governor, Dionisio Goncalves Rebelo Galvao.

By 1769, with Topass, the Dutch and several Timorese liurais giving them grief, the Portuguese moved the administrative capital from Lifau to Dili.

The Portuguese busily constructed forts in Dili and other strategic locations. Most of these had cannons pointing out to sea, a posture which failed to anticipate regular insurgence from the Timorese kingdoms.

If that wasn’t enough to contend with, Dili caught fire in 1799 and most of its valuable archives were destroyed. Also, the precious sandalwood – the main reason for trade and exploitation – was almost depleted. Coffee cultivation, based on the Dutch plantations in Java, began around this time but it would take some decades to get properly established.

By 1850, East Timor and its islands became a fully-fledged Portuguese colony, no longer a district in the province of Portuguese Macao. Dili was made a freeport for international trade.

The following year, Governor Jose Joaquim Lopes de Lima orchestrated his own trade – with the Dutch: the Maubara district for the islands of Flores, Solor, Adonara and Lamblem.

Such deals were not in a governor’s job description, however. De Lima was recalled, Timor and the islands went back under Macao control.

For the rest of the century, Timor shared much common ground with the larger island 600km away to its south – what was to become known as Australia. Portugal knew Australia was there and had visited often since at least the 1520s. Both lands were administered by European powers, their populations a mix of soldiers, bureaucrats, criminals and missionaries; both had skirmishes and massacres of the indigenous, and both were dumping grounds for political prisoners.

Dili was granted city (cidade) status in 1864. The first library was founded (at Lahane Mission) and another fire destroyed what was left of the archives.

The largest revolt against Portuguese rule, the Great Manufahi War, raged through 1910-12 under Dom Boaventura (that’s him on the 100-centavos coin).

And Portugal became a republic. After much internal shuffling, Antonio Salazar was made Minister of Colonies in 1930. It would not be until his death, 40 years later, that Portuguese colonies unraveled, and Timor was thrown into an altogether new form of occupation.

In 1939, a weekly flight began between Darwin and London, with a stop in East Timor, and Portugal authorised an Australian company to start petroleum exploration.

Two years later, Australian troops invaded Timor (despite Portugal’s World War II neutrality) to discourage the Japanese from using it at a base. The Japanese dutifully arrived and used Timor as a base. A small squad of Australians – with aid from Timorese criado – hung on to niggle the Japanese until the squad was evacuated, promising the Timorese “We will never forget you”, but they were in effect forgotten for the next half-century.

The Japanese threw the Portuguese into a concentration camp and slaughtered thousands of Timorese suspected of sheltering the Australians. A smaller number suffered at the hands of Australian troops. The Allies tried to air-strike the Japanese off the island; they scored a direct hit on Dili Cathedral.

By 1960, the UN added Timor to the list of territories to be de-colonised. President Sukarno told Lisbon the already de-colonised Indonesia had no intention of annexing East Timor. In Australia, Labor Party leader Gough Whitlam declared that the UN needed to guarantee self-determination to East Timor.

Things moved quickly. Portuguese president Caetano (who succeeded Salazar in 1968) was ousted by young army officers in the “carnation revolution” of April 1974. General Antonio de Spinola became president and recognised the right of colonies to become independent. But Spinola was forced to resign and was replaced by General Francisco da Costa Gomes.

As the last Portuguese governor, Mario Lemos Pires, arrived in Dili, Whitlam, now Australian prime minister, assured Sukarno that an independent East Timor would not be a “viable state.”

When Portugal decamped in 1975 after what amounted to many decades of “benign neglect”, there were brief, internecine skirmishes between various Timorese political factions. Fretilin (Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor) ultimately triumphed, formed government and declared independence on 28 November. The republic lasted nine days.

Indonesia invaded on 7 December and went on to annex East Timor as its 27th province. The Australian government turned its back on this, despite the murder of six of the country’s journalists. America and Britain continued to sell arms and aircraft to Indonesia.

What followed was 24 years of brutality and bloodshed in which an estimated 200,000 Timorese died – one third of the population – from murder, starvation and disease.

There was widespread lobbying internationally, by non-government organisations including the Australia East Timor Association, in support of calls by East Timorese for a plebiscite on their future. However, in Australia and elsewhere the general public did not think about Timor much until 1991, when the massacre of 300 young people in Santa Cruz, Dili, gave the international solidarity movement greater momentum.

In 1996 activist-diplomat Jose Ramos Horta and Catholic bishop of Dili, Carlos Belo, were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their work in support of self-determination.

Crippled by the global financial crisis and other discontent, Indonesia’s president Suharto was forced out in 1998 after three decades in power, and new president BJ Habibie, aware of the on-going cost to Indonesia of the East Timor conflict and seeking international acceptance of Indonesia’s occupation, agreed to a referendum on autonomy with Indonesia or independence. [GL1]

The lead-up to the referendum saw violence and intimidation by anti-independence militias organised and armed by the Indonesian military. The vote on 30 August 1999 had a 99 percent voter turnout and was overwhelmingly for independence: 79 percent rejected autonomy. The military and militias then sacked Dili, destroyed 70 percent of East Timor’s infrastructure, killed almost 1,500 Timorese and, in an attempt to downplay support for independence, forced 300,000 others, one third of the population, into western Timor, where they became refugees.

The Australian government was slow to respond, but eventually agreed to lead a UN-backed peace-keeping force (INTERFET). The UN and countless NGOs followed soon after and spent the next three years helping get East Timor onto its feet before finally, on 20 May 2002, it became the first new nation of the 21st century.

The road to independence has not been a smooth ride. There was widespread community violence in 2006, stemming from the sacking of disaffected soldiers, and in 2008 a raid by a former solider turned rebel left President Ramos Horta fighting for his life, while prime minister Xanana Gusmao narrowly avoided a similar ambush.

Other challenges have included the development of the valuable oil and gas reserves in the Timor Sea and obstruction from Australian interests, including the government.

Timor-Leste has had a fraught history. It still suffers from high unemployment, poor health and education services, and the uncertainties of an immature political system.

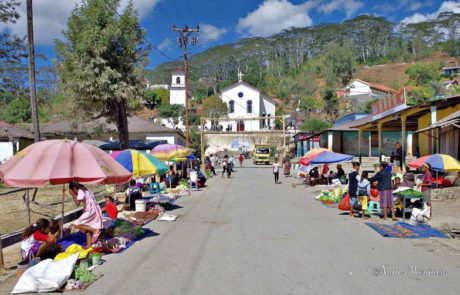

But the East Timorese are a happy, friendly and optimistic people, despite their nation’s travails.

Other reading:

http://timor-leste.gov.tl/?p=29&lang=en

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_Timor

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/geos/print_tt.html